Many manufacturers are facing booming demand as the global pandemic recedes. But fulfilling orders to meet this growing demand is often challenging because of ongoing supply chain disruptions, especially of critical components.

When capacity is limited, even temporarily, how should manufacturers think about which orders get priority? Obviously you must meet contractual obligations first — but beyond that?

In this post we propose a way to approach this analytically. There are three dimensions to consider:

- Who is the customer and how do they fit in your strategic priorities?

- Can your organization make and deliver the order within (or close to) the customer’s window?

- Should the comparative profitability of orders be a consideration?

Who Is the Customer?

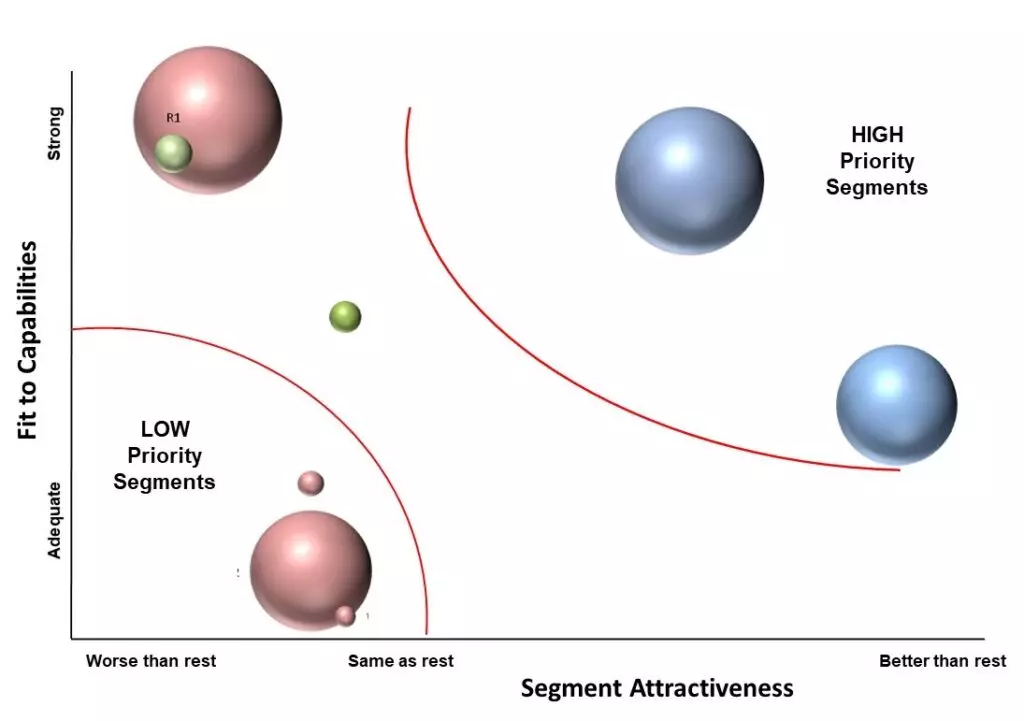

One way to prioritize by customer is to refer to the customer segmentation and prioritization of the segments — which should have been set by the leadership team of the business as a whole. Orders from customers in high-priority segments should be prioritized over orders from customers in lower-priority segments, all else being equal (which it rarely is; see additional factors below). Segmentation and prioritization of customers is a critical element in deciding where to compete and how to win.

Priority segments may be smaller but faster-growing than larger, mature segments; and allocating production to customers in such segments when industry capacity is stretched may enable you to take market share. Moreover, growth segments may have “longer legs” and should be nurtured for the future health of the business.

But an intervening consideration is the loyalty of longtime customers — shouldn’t customers who have stuck with you receive higher priority? Of course — assuming there has been reciprocity in the relationship over time. For example, if you’ve been a secondary supplier for a long time to a customer who has given you orders even when they might do better by consolidating your volume with their primary supplier, well, this could be the chance you’ve been waiting for to get a larger share of their business. Of course, many such relationships will be in high-priority segments to begin with, as most companies are willing to invest to maintain backup supplier status only in businesses they are trying to grow. Another form of customer loyalty is their demonstrated willingness to work with you to get through tough spots — for example, will they expedite PPAP loops so alternative assembly lines may be used? Flexible, pragmatic customers should get extra consideration.

Ability to Make & Deliver

In combination with customer prioritization, it’s necessary to consider whether the order can be completed without painful delays. If you can’t manufacture the entire order with materials on hand, consider the risk that you won’t be able to get everything needed. If capacity is limited because of supply chain disruptions, it’s dangerous to assume that JIT supply chains are operating as usual. (The auto manufacturers, for example, cut orders to chipmakers in the first half of 2020, then couldn’t get that capacity back once it had been allocated to higher-margin consumer products. The resulting parts shortages have forced many auto makers to pause production.)

However, it’s the delivery aspect that sometimes gets overlooked: it does little good to manufacture the order if you are unable to deliver it as expected to the customer (unless you can invoice at the factory gate). Ocean shipping has been a particular bottleneck.

By considering together both customer priority and ability to make and deliver, you can arrive at a practical (initial) prioritization of orders. It may be better to complete orders for a somewhat lower-priority customer than to be unable to deliver completed orders to a higher-priority customer.

Comparative Profitability

Only after considering both the customer and the ability to make and deliver should manufacturers take the profitability of orders into account. Although it’s tempting to put comparative profitability first, that can be strategically shortsighted — it can be better for the long-term health of the business to fulfill less profitable orders for higher-priority customers (e.g., those to whom you are a tertiary supplier, but in an attractive segment you’ve targeted for taking share) than more profitable orders for lower-priority customers, or orders you can manufacture but not get to the customer.

As an experienced manufacturing leader who had been through many business cycles told us, it’s most important to have a plan for when commitments outstrip capacity — “that’s not the time to have a production supervisor prioritizing who gets what, when. If you have to ration capacity or reorder priorities, it should be done with a script and a process that can be defended.”

A Key Consideration: Transparency and Openness

Manufacturers of large capital equipment (such as bulldozers, locomotives, tractors) often promise “slots” in the production schedule to particular orders — often in return for ordering with plenty of lead time, or for selecting certain options. It’s risky to change the schedule without being open about it, but the degree of risk depends on what you committed and how transparent you were in the first place. Customers are generally more concerned with the timing of their order than with their place in the production schedule, but if you committed to a place, you should break that commitment only reluctantly. (What do you think? Please weigh in with a comment.)

In addition to prioritizing the orders you get, there are several ways to shape the demand (and resulting orders) to better suit your capacity to deliver. We’ll address those in our next article.