It’s widely accepted that for traditional manufacturing leaders to continue to thrive, they need to become solution providers — not solely product manufacturers. They must seize the high ground of emerging information, communication and analytical capabilities embodied in the “internet of things,” and incorporate the necessary hardware and software into their products. They must re-think how they respond to customer needs, fully align all product organizations around addressing these needs, and change the way they define development programs and allocate R&D dollars. In particular, they need to:

- align priorities across product groups and regional organizations, both across and within the customer’s production assets;

- understand the customer’s production economics;

- and then employ data and analytics to identify not just product improvements, but process improvements for customers.

This reorientation represents a fundamental change in the how to win of strategy, as well as the where to compete.

But implementing this strategic change is difficult if the company is organized around its products, rather than its customers and their tasks — and the challenges begin with how the company is organized and operated.

For long-established manufacturers, most product development is traditionally performed within distinct product-based organizations — for understandable reasons. But having those groups individually prioritize all R&D for their products risks the over-improvement of existing product forms and makes it difficult to address customer needs that span product types.

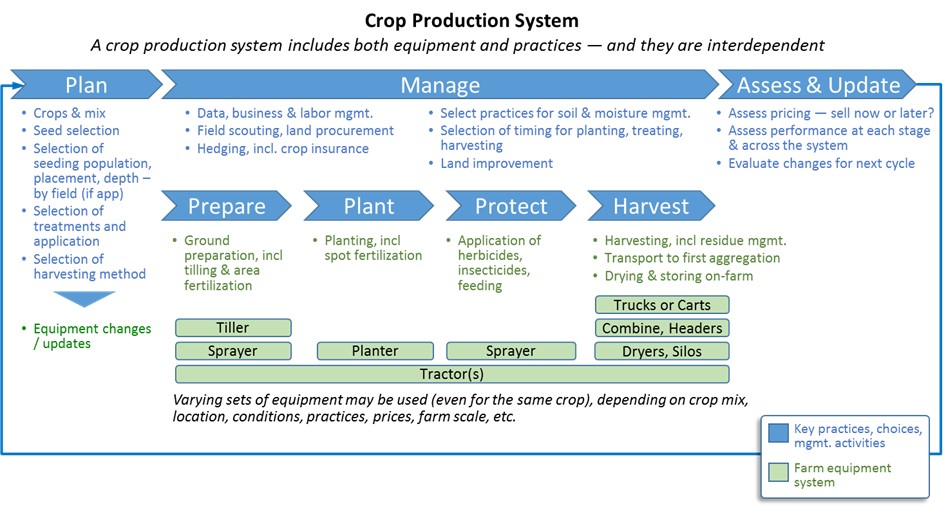

This problem becomes more acute when the company sells a collection of products to be used together in a “production system” (the full set of practices and products employed by the customer to produce a product). In industries such as road construction; airlines; mining; agriculture; building construction; or forestry (to name just a few), the range of equipment needed can be quite extensive and varied. Customers obtain their preferred equipment, consumables, and information from various suppliers who tend to specialize in each. The leading capital equipment suppliers generally seek to maximize their share of the equipment supplied for the production systems they serve, offering incentives to customers to purchase more of their equipment from them instead of assembling a heterogeneous mix. They do this with favorable financing, and increasingly by making their products work better with each other than with the products of others. But product organizations even within the same company face challenges that make it difficult to ensure their products will work together to maximize performance in the customer’s production system. This problem will only become harder as products become smarter and more connected, and the information layer spanning production systems becomes thicker, broader, and more valuable.

Organization by product presents several challenges to a strategy shift to solutions:

First: Within a single supplier, as each product organization prioritizes developing the features and capabilities that most improve their products’ performance (and their organization’s financial performance), it becomes difficult to coordinate across product organizations to deliver integrated capabilities to customers.

For example, in agriculture, consider a production system for a particular crop. Tractors, planters and combine harvesters are required equipment (among other things). The tractors and planters may be high priorities for the tractor and planter organizations, but the market for the harvesting equipment best suited to that crop may not be sufficiently attractive to the harvesting organization for them to fund development ahead of pressing needs for another crop. This disadvantages dealers as they seek to grow their share of customers’ spending, and leaves openings for competitors to exploit. Absent a way of prioritizing particular crop production systems and then picking where within them you will compete, important choices are made by default and not on purpose.

Second: Having each product group prioritize their own projects risks missing emerging customer needs. Indeed, some customers’ most important needs can only be seen by companies looking to innovate across the entire production system, decomposed into the many “jobs” that a customer needs to accomplish. For example, in agriculture, seed selection with precision planting may bring the greatest value to the customer, but it can be difficult to justify investments in those if you must take the funding from the larger product forms (e.g., tractors and harvesting combines) which generate more margin for the company.

Third: Focusing R&D on individual product forms which together make up (the equipment portion of) the customer’s production system also makes it more difficult to realize the full value of smart, connected products (see Porter & Heppelmann, HBR Nov 2014) — because typically there is no reward within one product organization for absorbing costs when the value is mostly realized by another product organization. For example: sensing and data collection (related more to production system performance than combine performance) are difficult to justify in the context of funding a combine project, especially if the benefits accrue to another organization (e.g., precision planters). Product organizations are more likely to invest instead in the features and capabilities of immediate interest to their higher-margin, most advanced customers — thus falling prey to “the innovator’s dilemma.” Additionally, much of the benefit of Big Data will be realized by changing practices in the customer’s production system (e.g., timing, inputs, processes). Seeding and feeding practices may have large effects on costs and productivity — yet may not necessarily require different equipment, but rather data collection and analysis. Equipment manufacturers who neglect such opportunities risk becoming marginalized.

John Deere recognized the risk, and began the strategic shift to being a “Smart Industrial.” As part of that shift they introduced a new operating model — organized around production systems; the technology stack; and lifecycle solutions. Deere’s reorganization has been extensive, because leadership recognizes the value of organizing to deliver the business strategy.

#manufacturingstrategy #orgstructure #strategy