by eos consulting | Feb 22, 2021 | Manufacturing Strategy, Uncategorized

If you Google manufacturing strategy, one of the top results is a Harvard Business Review article — from 1994. How can it rank so high given its vintage? The reason: it gets clicked on a lot — not only because it was written by two authorities on the subject, but because its insights remain on-point and highly useful (even after twenty-five years).

Let’s start with what they say about manufacturing strategy and strategic flexibility. Hayes & Pisano argue that:

In a stable environment, competitive strategy is about staking out a position, and manufacturing strategy focuses on getting better at the things necessary to defend that position. In turbulent environments, however, the goal of strategy becomes strategic flexibility. Being world-class is not enough; a company also has to have the capability to switch gears—from, for example, rapid product development to low cost—relatively quickly and with minimal resources. The job of manufacturing is to provide that capability.

That seems like kind of a big ask, doesn’t it? Perhaps it’s less daunting if we break it down into manufacturing capabilities that can deliver strategic flexibility to the business, such as:

- Agility & Responsiveness — the ability to handle changes in production volumes or product mixes; and to react quickly and effectively to product design changes, raw material changes, or customer order and delivery requirements (product options, order changes, delivery modes / timing / locations)

- Resilience — the ability to withstand shocks or rapid changes in exchange rates, labor or input costs, trade conditions, shipping rates, pandemics, and other operational disruptions

- Integration — the ability to incorporate new processes, products, or product architectures into the manufacturing operation

- Innovation — the ability to develop and deploy new or unique manufacturing processes to dramatically improve manufacturing performance

- Control & Improvement — the ability to direct and regulate operating processes, correct errors or inefficiencies, and to improve manufacturing performance

Such capabilities depend on much more than manufacturing sites, equipment and technology. As Hayes and Pisano point out, “a company’s capabilities are more than its physical assets. In fact, they are largely embodied in the collective skills and knowledge of its people and the organizational procedures that shape the way employees interact.”

Assembling the right combinations of assets, people, and process to deliver a desired capability — such as resilience to trade disruptions or global pandemics — takes time, commitment, and judgment.

And of course there are tradeoffs: low-cost production which relies on offshore suppliers can be brittle, subject to supply shocks (as many learned during the pandemic); yet steps to increase resilience can also increase costs. Production agility, if achieved with highly flexible lines, can also be expensive (but there are other ways to do it…).

These choices should be made in view of the business strategy — particularly the “how to win” elements. And good decisions about how to win can’t be made in ignorance of the actual or potential capabilities of the manufacturing organization. In fact, by “expanding the range of their manufacturing capabilities, [manufacturing leaders] increase their strategic options” for the business.

Which is why manufacturing leadership should be engaged in the business strategy.

by eos consulting | Oct 14, 2020 | Manufacturing, Uncategorized

Consumer and medical goods shortages during the global pandemic have inspired some media backlash against Lean Manufacturing practices; the Wall Street Journal even published an article saying we should “blame lean manufacturing” for paper towel shortages. Yet most manufacturing leaders have been taught (or learned the hard way) to “buffer or suffer” — that is, carry some inventory of key parts or materials, lest production halt for a simple stock-out. But inventory buffers are costly, and more than just the cost of capital: there’s also storage space and the risk of damage or obsolescence.

Demand or supply shocks are particularly challenging to process manufacturing (paper, paint, etc.), because winning in such products generally requires scale — often huge scale, expensive and time-consuming to build. But discrete manufacturing is vulnerable as well, especially if capacity (robots, material handling automation, assembly lines) is expensive.

This WSJ article provoked responses from Lean experts and practitioners, chiefly that:

- Lean practices work best with steady (or predictable, or controllable) demand, and that the pandemic created surges in demand that predictably created shortages; and

- Over the full cycle, Lean Practices (as demonstrated by Toyota) save much more than they cost.

The critics complain that producers are unwilling (or unable) to quickly add capacity when demand surges, and the rest of the supply chain is insufficiently buffered against demand (or supply) shocks. This restraint is attributed to the high cost and time required to add capacity (especially in process industries), but it also reflects managers having learned their lessons while playing the “Beer Game” in business school. The Beer Game is an exercise wherein teams of four (representing the factory, distributor, wholesaler, and retailer) compete to deliver beer to their customers at the lowest total cost over the course of the game (both stockouts and excess inventory incur penalties). End consumer demand is steady throughout the first part of the game, then doubles for the remainder. Inevitably, that single step change in demand generates a huge over-response in the system. Players learn that the best way to avoid “whiplash” in the Beer Game is to be slow to react to demand shocks.

So it is not surprising that many goods (including medical PPE and more) are still in short supply, even nine months into the pandemic. So, is there anything to be done, any adjustments that can be made? How should business leaders decide whether to stay (or become) lean, or instead build in more buffers to cushion against shocks? And how far should you go? The answer lies in your business strategy, which should drive your manufacturing strategy.

It starts with your value proposition — why your customers buy from you instead of your competitors. This is a key element of any business strategy. Generically, firms compete on the basis of price, differentiation, or customer intimacy.

Price includes not just cost to the customer, but also terms and transaction costs. To be sustainable, competing on price requires a secure cost advantage. Differentiation can include product quality (such as materials, durability, reliability), features, and performance. The value of the brand (where it means something to buyers) is also an element of differentiation, as is local production – really anything that a customer values and sets you apart from the competition. Customer intimacy is about the relationship, support, and responsiveness; it can include product scope, range, and customization; as well as order windows and delivery policies. (Customer intimacy can also be thought of as a dimension of differentiation.)

Customers don’t select one or another so much as they make tradeoffs between them: e.g., “good enough” quality at a “low enough” price, with adequate delivery performance. Moreover, not all customers make the same tradeoffs — although customers in particular segments may make similar tradeoffs.

If your most important customer segments will trade off the lowest possible price in return for product availability and reliability of delivery, then you should consider taking on the added costs of buffering finished goods and/or critical inputs. But if your targeted customer segments instead value the lowest price more than product availability (perhaps they prefer to hold their own inventory), then it’s worth risking occasional shortages to keep your operations as lean and efficient as possible. (In either case, you need to consider what your competitors can do for those customers — if they can accommodate those customer needs better than you, you’ll need to shift the basis of competition.)

Another way of handling these tradeoffs is to build flexibility into your sourcing and manufacturing, not by buffering but by configuring your operations to flex with supply or demand shocks. In the simplest case, lean methodology has always insisted on the need to identify and qualify additional suppliers — and many firms always source from one or two alternate suppliers as well as their primary, to ensure additional supply is available. But some disruptions (like hurricanes or pandemics) affect all regional suppliers, not just one.

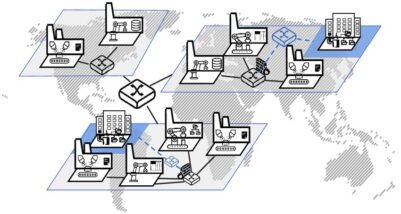

You can also build flexibility into your manufacturing network, especially if you have modularized product designs (products consisting of assemblies of interchangeable modules), by:

- Manufacturing modules in more than one location, so production in one location can cover for outages or cost surges in another

- Ensuring those manufacturing capabilities are in differing trade zones and supply bases

- Carrying some additional production capacity in those locations

Modular product designs enable you to offer more product variety, by offering different permutations of modules — which can also help limit the size and scope of inventory buffers.

Lastly, it need not be entirely up to manufacturing to respond to demand shifts: demand can be shaped to better fit manufacturing capacity. Makers of large capital equipment, for example, often offer discounts for early orders, or price options consistent with the availability of parts to make them.

Lean practices have attracted scrutiny as a result of the disruptions caused by the global pandemic. But whether you should modify what you are doing — and how — depends not just on costs, but on your business strategy.

Read more: Manufacturing Strategy

Read more: Manufacturing Strategy in Today’s Volatile Trade Environment

Read more: Hitting RESTART After the Pandemic

by eos consulting | Aug 11, 2020 | Manufacturing, Uncategorized

We’ve been talking about challenges for incumbent manufacturers, and suggested in our last post that for manufacturers to thrive, they need to command privileged positions in at least some of the business ecosystems in which they participate.

A privileged position means:

- Being core to or at the center of the ecosystem; or

- Owning vital elements of the ecosystem (standards, technology, proprietary software, etc.)

We suggested some ways to achieve that, among them:

- Ensuring that if there’s value in making your product ‘smart’, you play an important role in doing that — controlling or influencing the development of software, APIs, capabilities, standards, etc.

- If your product has software in it, owning its design and development as much as possible, especially for controls.

But designing and developing software poses distinct challenges for incumbent manufacturers — even if they don’t try to do it themselves.

In particular, incumbents’ existing development processes for many industrial products (such as electro-mechanical devices ranging from valves to combine harvesters) are likely much slower than for software & electronics — and for good reason. Such products (especially large ones) often comprise multiple integrated systems and components. Changing one affects others, and can have unpredictable effects on the performance of the entire machine. Moreover, a design change means changing manufactured parts and/or their fabrication — which, especially if it involves suppliers, can be slow, risky, and costly. Accordingly, incumbent manufacturers have learned how to update their products carefully and with manageable pacing.

Software development cycles, on the other hand, are much shorter. Software is easier to edit, test and replicate (even if the consequences are just as unpredictable, if not more so). But precisely because it is easier to edit, software development processes have come to be dominated by modularity, agile methodology, and rapid development and deployment.

Harmonizing these differing development processes across a set of design projects for a specific product is not easy, even (or especially) if the software development is outsourced. Except in cases of an entirely new product form, the physical product exists already, and the software project is about adding or upgrading sensors; adding communications in or out (from those sensors, for example); or automating (and/or optimizing) controls. Hardware engineers do not generally write software, so the first challenge is setting and maintaining execution schedules between hardware and software engineering teams (coordination only between individual engineers is often insufficient). A technical surprise or a shift in funding priorities can disrupt timelines, leading (in the worst case) to product delays or even incomplete (or buggy) solutions coming to market. In addition, design changes to the physical product and the software can get out of sync, again requiring time and often-scarce resources to reconcile. (Your software people may be spread thinner than you realize — especially if they must work with several product families.)

But there’s a deeper issue which may produce or exacerbate execution challenges: it’s not uncommon for requirements to change (or to be too vague), leading to misalignment between hardware and software teams. This especially plagues projects where the software component is outsourced or developed by a different unit of the company. It may even be unclear who owns the user experience, or the entire solution’s architecture and requirements.

In addition to adding cost, time delays are a frequent outcome of these challenges; yet for a large industrial product, missing a competitive product upgrade cycle (or two!) can be fatal to market share and/or profit margin.

So, what can be done?

- Start upstream from execution, with a shared vision across hardware and software of the value proposition for what you’re doing. Are you adding software-enabled features because the competition has them, and you must keep up? Ask yourself what the new capabilities will do for the customer, and whether/how that fits into your value proposition. If you must catch up, you might as well leapfrog — but only so far as you are meeting a real customer need, and not just trying to “out spec” the competition. (Yet leapfrogging can be a dangerous temptation — you are likely to take on additional technical risk, as well as marketing / channel challenges. And you had better be confident about profitability.)

- Ensure the product requirements are specific, measurable, and deliver the value proposition. Work together and be willing to listen to each other — often, the software team can suggest capabilities the hardware team didn’t realize were feasible. Most important, when requirements change (as they often will over the course of a project), don’t assume everybody is aware. Revisit the timeline and collaboratively make any needed adjustments.

- Consider developing a realistic, actionable product roadmap, incorporating some high-probability variants (e.g., funding cuts). This can align expectations and enable planning for contingencies. Perhaps most important, it enables you to be proactive — not re And the roadmap needs to reflect — and reconcile — the differing challenges of hardware and software development (e.g., seasonal product testing).

- Establish program governance across all the participating organizations for the set of projects together delivering the product update. This doesn’t have to be extensive or bureaucratic, but it does need to include:

-

- A joint repository of the project documents, including staffing, leadership, schedules, and requirements.

- Who decides what, and how conflicts are managed (“decision rights” — especially over product architecture, standards, and shared systems). And not just in theory — the organization must honor the process and “walk the talk,” especially when it comes to balancing the interests of not only hardware and software, but of design, manufacturing, and sales & marketing. (For example, who owns the specifications of the CAN bus on a vehicle? Especially if it is the factory which must carry the cost of a better one?)

- How communications between software and hardware teams will happen (e.g., when software teams change delivery dates for product features, how they will ensure the hardware teams know about it so they can plan).

Incorporating intelligence and connectivity into industrial products and components can be challenging, but it also opens new opportunities (as well as challenges) for incumbent manufacturers. Failing to do so can mean eventual relegation to commodity status. The manufacturing companies that will thrive in the future are likely to be “smart industrials.”

For more about operational governance, please see here.

by eos consulting | Jul 2, 2020 | Uncategorized

In the 2007 movie There Will Be Blood, a character explains how directional drilling can drain the oil reservoir under someone else’s land. “I drink your milkshake!” he proclaims, to the dismay of the character whose oil profits have vanished. With similar dismay, many manufacturers have seen their profits drained away by other companies.

Many of the great American manufacturing companies of the 20th century have fallen on hard times. GM, US Steel, General Electric and more are now shadows of their former glory. Those that have thrived in this century (such as Apple, Intel, Honeywell, John Deere, or Rockwell Automation) tend to either lead or play major roles in one or more of the business ecosystems in which they participate.

Consider Apple, now one of the world’s most valuable companies as measured by market capitalization. Apple makes the lion’s share of profits earned in the smartphone industry, and they are the most profitable large-scale OEM in the world. Especially for a manufacturer, Apple is very profitable.

But is Apple really a manufacturer? They outsource nearly all their production and assembly — Apple does not actually build their phones, pods, computers, or much of anything else in their product suite.

If they are not, how then do they manage to drain the profit pools of most of the manufacturers in the smartphone industry? Why can’t most of the companies who actually build all those chips, iPhones and iPads extract more value from Apple?

Only by holding the commanding heights (privileged positions) in a thriving ecosystem, including a manufacturing ecosystem, is Apple able to collect most of the profits in the smartphone business.

The famed Apple product and services ecosystem consists of devices (mostly iPhones, iPads, Mac desktops & laptops, and wearables (Apple Watch, AirPods)) and their key components (especially chips); operating systems, standards, & APIs; software applications and services; and a software development community. The attraction of the ecosystem is the interoperability and ease of use of its elements — “it just works.”

Apple’s manufacturing ecosystem is also extensive. Apple designs its products, sets standards for and governs much of the supply chain several layers deep, and has other companies in the ecosystem manufacture components and assemble most products. Key hardware and manufacturing members of the ecosystem include Foxconn, TSMC, ARM, Intel, AMD, Samsung, LG, NVIDIA, Broadcomm, and many more.

Apple governs this ecosystem by occupying the key roles: As the OEM (and direct seller of many devices), Apple controls access to the customer. As developer of the operating systems and core applications, Apple sets the standards, defines the APIs, and controls the platforms on which Apple products and services operate. As designer of the products and the systems-on-chips (SOCs), Apple optimizes both hardware and software to achieve better performance for cost. As system integrator, at both the device and ecosystem levels, Apple is able to ensure that participation in the Apple ecosystem is always on Apple’s terms.

Because Apple controls both the software and hardware, they are able to sell software embedded in proprietary hardware — and realize the profits on either the hardware or the software (depending on what is tax-advantageous).

Apple did not start off controlling their own smartphone ecosystem. Indeed, they were late entrants to smartphones, with relatively low volumes — at first. But Apple crafted its smartphone ecosystem, then over time merged the rest of its offerings into it. This demonstrates one doesn’t have to be the market leader (at the time, that was Nokia— remember them?) to begin building a viable ecosystem.

Apple’s example has important implications for other manufacturers: if you want to earn sustainable returns, you too need to figure out how to define and control key roles in viable ecosystems. This is especially urgent in the age of the Internet of Things (IoT) — as more physical products are imbued with networking capabilities, “dumb” (no computational or networking capabilities) products are likely to be increasingly commoditized.

Manufacturers should consider:

- Ensuring that if there’s value in making your product ‘smart’, you play an important role in doing that — controlling or influencing the development of software, APIs, capabilities, standards, etc. (Note this doesn’t mean “make your product ‘smart’” if there’s not a customer segment willing to pay for such capabilities; internet-connected washers come to mind). But industrial valves, for example, can usefully be enhanced to be both sensors and digital controls.

- If your product has software in it, owning its design and development as much as possible, especially for controls. Any performance-enhancing integration of your product’s controls with others in the ecosystem strengthens your position.

- Commanding the integration nodes to and around your products. Proprietary physical interfaces and proprietary APIs can both deliver great leverage, even in an ecosystem not your own. (They must deliver real value to your customers, though.)

- Ensuring that it’s your hardware and/or software used at the points in the system that most drive performance. In an engine, for example, the fuel controls, emissions aftertreatment, and turbocharging are important drivers of an engine’s performance — and there is an entire frontier of optimization opportunities. Finally, to the extent that an important platform is part of the ecosystem (operating software, an order fulfillment system, a particular piece of hardware), try to move up from connection and compliance with it to influence on it.

These are fundamental issues strategically: Where to Compete, and How to Win. “Where” is not only which products, for which customers, in what markets and geographies; it’s also where in the value chain and where in the ecosystem. “How” includes all the strategic actions described above, but especially regarding ways to be a more important player in the ecosystems in which you participate. It’s not going to be enough to be “the low cost producer.” Not for long, anyway.

by eos consulting | May 28, 2020 | Uncategorized

The industry in which you compete may not emerge from this pandemic the way it entered. Some industries may undergo structural change (e.g., healthcare: telemedicine and long term care, travel, tourism, etc.) while in others the required adaptations will be less dramatic (reworking supply chains will be common). Yet many companies, once the immediate crisis has passed, will revert to the organizational routines and decision-making processes deeply embedded in their culture. Their strategic response will likely be “more of the same, but try harder!” This predictability will increase risks for the complacent and present opportunities for the agile.

So how do your competitors think they can count on you reacting? Are you vulnerable to them exploiting your predictability?

Periods of disruption create opportunities when the participants or the “rules of the game” change, or when new or emerging technologies are accelerated into broader use. This pandemic may end up changing the nature of competition in many markets, as well as who participates; it has already accelerated the adoption of distance learning, telecommuting, and virtual business.

Let’s start with market structure: many industries will become more top-heavy as smaller players are driven out of business and acquired by larger firms. This happened after the 2008 financial crisis, and is likely to be even more widespread this time, creating opportunities for more agile incumbents.

“A key advantage was that everything was cheaper in 2007 and 2008. ‘We were able to acquire smaller companies for very favorable multiples since there was less competition bidding for these businesses. Moreover, their limited access to capital stunted their growth allowing us to gain leverage very quickly once they were part of XL Marketing,’ said David A. Steinberg, CEO of Zeta Interactive” (formerly XL Marketing). [Citation]

If your strategy has relied on selling to smaller firms at better margins — you might find that you will have fewer customers.

Cross-border trade (and reliance on low-cost Chinese suppliers) will face challenges, as the trading environment shifts to become more protectionist — affecting not only medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors, but basic inputs across a range of industries. For companies relying on tightly integrated supply chains originating in China, the costs and time required to diversify those supply chains may open up opportunities for competitors less embedded in China. What was once a strength can become a weakness. Even in the absence of limitations on free trade, changing foreign exchange relationships may make it easier for previously tertiary competitors to become quite troublesome. Can they rely on you to just “ride it out”?

I recently wrote about how the pandemic requires a rethinking of where businesses choose to complete and how they will win. That article was introspective, looking from the inside out – focusing on what a business should be thinking about amid a shifting and unknown post-COVID landscape – unprecedented in our lifetimes (see article here). Now, let’s look outside-in: how do competitors view your position and strategy? Are you too predictable as your industry adjusts to a post-pandemic world?

Success in the marketplace is determined by the alternatives available to your customers. Those alternatives are generally your competitors’ products and services (with associated pricing and availability). Thus, your strategy is only as good as it affords your organization a benefit (to you or to customers) that competitors cannot match.

So, if the structure or the basis of competition in your industry shifts as a result of the pandemic, what do your competitors think you will do? Can they rely on you resuming “business as usual”? Organizational inertia dictates that this is probably the default position. And if you had an advantage pre-pandemic, maybe maintaining your strategy and organizational routine is appropriate. But, structural changes may prompt competitors to try to break the binds of that inertia (and count on you not to do so). One example might be re-regulation. Certainly the pendulum is swinging back in that direction as more industries and businesses are thrown lifelines (with strings attached). What might this mean to your industry? Is there a way that you can leverage regulatory oversight to your advantage? What if a competitor does so?

If you suspect that the pandemic may shift the terms of competition in your industry, how should you proceed? We recommend starting by documenting the following:

- Identify changes that may occur in your industry as a result of the pandemic: Will trade barriers or tariffs become a factor? How? For whom? Will reliability of supply become a more important purchase criterion? Will certain customer segments shrink or grow? Will competition in the industry increase? Could aggressive new competitors enter?

- Who could benefit from the change(s) — you? Competitors? New entrants? For example, many manufacturers have realized that they can produce PPE and ventilators – are some of them new competitors (or suppliers) for medical supply companies? What current competitors will most likely not survive or need to alter their product/service offerings?

- What organizational habits of mind could prevent your firm from adjusting to these changed circumstances? What about your competitors?

- Finally, think about talent – with employment in turmoil and many workers furloughed, is this an opportunity to acquire skill-sets that will advantage you in the future? Better than having a competitor do so!

Assess where your relative strengths might enable you to pursue certain opportunities better than competitors. Then, formulate a hypothesis around each potential and commit to testing each (a few is probably sufficient). Write down “what would I have to believe” in order to move forward with each hypothesis.

This exercise may provide tremendous insight – in fact, the very process of thinking it through and committing it to paper will be valuable in itself. It is also very likely that you will discover opportunities that your competitors will not (or cannot) act upon – relegating them to status of the sitting duck.

by eos consulting | May 28, 2020 | Uncategorized

While companies around the globe are thinking about how to restart normal operations, the initial focus will undoubtedly be tactical. Forward-looking leadership teams will realize that now is the time to re-think their company’s business strategy to maximize chances for success over the intermediate to longer term.

It is likely that strategic plans established during the record global economic expansion will no longer apply in a post-pandemic environment. At the very least, financial projections outlined in those plans are no longer realistic. But the challenge is not limited to making better forecasts — the ground has shifted fundamentally for many businesses. Some customers and suppliers will recover slowly, others not at all. Industrial ecosystems have been disrupted across the globe. Business strategies will need to adjust — and quickly.

So where to start? Simply stated, strategy is about choices: what is the company all about and why do you exist? Where do you choose to offer your products and services, and to whom? Why? What are those products and services, and what business models do you employ? Think of these questions as links in a chain, and let’s consider each in turn.

What are your goals and aspirations?

Is your fundamental mission still intact? Has your definition of success changed? Perhaps not, but there is a chance that you will need to re-scope these for the new environment. After assessing where you choose to compete and how you will win in target markets (see below), you might well determine that an adjustment is necessary. You may need to raise your sights, or narrow them. If you have not had clear company aspirations, mission or vision, now is the time to develop that clarity.

Where to compete?

“Where” is not only about geography, but also about customer segments and sales channels. This is an arena where many companies will want to make modifications. Are some types of customers that you currently serve across markets globally going to be different in the future? Will the market demand be different from historical trends? Will there be dramatic swings necessitating focus on certain markets and/or customers and not others? Will the jobs change that customers perform with your products and services? Will new market opportunities present themselves that were not apparent before? Is there an opportunity to build market share by countering competitors’ moves and filling voids in markets where they choose not to focus? Very likely, the answer to some of these questions is a resounding, “yes”.

By clearly articulating the specific markets and their respective customers and then prioritizing their relative attractiveness and the capability of the company to serve these markets, the result is a very targeted understanding of where the company should (and should not) compete. For example, your products or services may remain the same, but prioritized geographies may need to change, or your channels may need to evolve to accommodate more business-at-a-distance.

How to win?

Once you understand where to compete, the next step is to determine how to do so in each selected market. Will you need to rethink the appropriateness of the products and services that you provide for those markets as determined above? Will different products and/or services be required? Could business models need to change? Do value propositions need redefinition? Will the company’s production assets (supply chains, factories, etc.) need to be reconfigured? How might the organization structure or operating model need to evolve?

These strategy elements are interdependent — when one changes, others may become misaligned or inconsistent. By answering these questions for each defined market, you provide strategic clarity. Most likely, some of these elements have changed. This necessitates a thoughtful review of your business strategy.

At this crucial moment — how strong is your strategic plan? Returning to the metaphor above, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. This pandemic is a unique and unprecedented disruption that has left no individual or company unaffected. Your future success will depend upon how you respond. Companies that realize this, take the time to fortify these links, and make appropriate modifications to their strategic plans will be the ones that win in tomorrow’s marketplace.